Event

New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collections of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY

Event

New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collections of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY

(Temporary) Collection of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY: Eve Meltzer

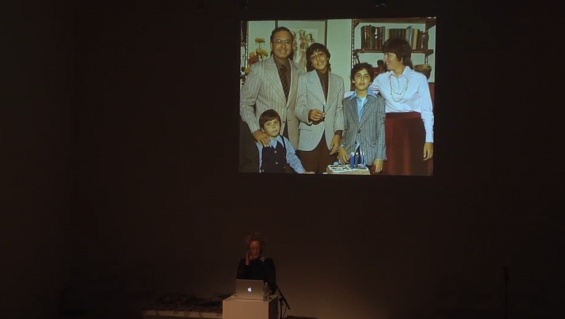

Eve Meltzer, lecture as part of “New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collection of Ideas,” 2015. Image: Travis Chamberlain

In the sixth of seven successive perspectives from artists, choreographers, curators, dancers, and scholars on the term “choreography,” here Eve Meltzer, an art historian and scholar of various philosophical and theoretical discourses, contributes her thoughts on the topic to the Six Degrees series “(Temporary) Collection of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY.” As part of a daylong symposium in February initiated by the R&D Seminar’s participants, Meltzer presented a short talk wherein she explored choreography vis-à-vis her own work. The Seminars asked Meltzer to develop her public presentation in tandem with this short text.

Meltzer is currently working on a book that examines what she calls the “psycho-photographic consistency of group belonging.” Interpreting the way that a subject’s psychic life is organized or inscribed by invisible attachments as a form of choreography, Meltzer examined the introductory sequence for the 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans as a case study in her presentation.

One could say that psychic life is blindly choreographed by invisible attachments. We are inscribed, our affective gestures already written in advance. Can the notion and practice of choreography illuminate this blindness, its theatrical repetitions, and the scenes it produces and reproduces—both psychic and photographic?

I am interested in the point of contact between, on the one hand, psychic attachments—particularly primary attachments, feelings of first belonging—and, on the other, photography and the forms of visibility afforded by its medium, practice, and discursive life. Here I focus on the former. By “attachment,” I refer to the notion that the making of subjects involves a formative affective relation, or “primary passion,” between those who are subjected and those who hold out the promise for existence itself. Attachment is what adheres the subject to his or her own subjection and to those in power, those who subtend one’s sense of “what it means to keep on living on and to look forward to being in the world,” as affect and political theorist Lauren Berlant has written. “All attachments are optimistic,” even if they don’t feel so; what Berlant means is that the subject “leans towards promises” contained in objects, relations, things, and so on, for the very reason that the feelings they make possible ensure her sense of continued being.1

Here I am working with the notion of “passionate attachment” theorized by gender and political theorist Judith Butler in her 1997 book The Psychic Life of Power.2 There, she explores the exploitable nature of the desire to survive. Her notion of passionate attachment turns on the claim that there is “no possibility of not loving where love is bound up with the requirements for life”—so subjects become attached to other subjects as a human imperative.3 For, as psychoanalytic theorist Jean Laplanche explains in his reading of Freud, affectivity grows out of the instinct for self-preservation, in which the former is “propped upon” the latter.4 Attachment is, therefore, a condition of psychic and social survival because, as Butler explains, “the desire to persist in one’s own being requires submitting to a world of others that is fundamentally not one’s own.”5 We are thus passionately attached to the subordination that defines our subjection, because while power subordinates, it also gives us being.

Importantly, however, our most passionate attachments are also those that we can never “afford fully to ‘see,’” Butler explains. They must both “come to be and be denied,” because to turn back upon one’s self is precluded (and its vantage, occluded) by the effects of attachment itself.6 This invisibility works in the service of repetition, compulsive reenactment, and suffering.

These are some ideas I am working through to begin to theorize the psycho-photographic consistency of group belonging. Andrew Jarecki’s 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans—a film that presents the different beliefs surrounding the child molestation case against Arnold Friedman and his then-eighteen-year-old son Jesse Friedman—also represents, through its use of photographic, videographic, and filmic pictures, one family’s mode of putting pressure on the passionate attachments that choreograph their relations.

The opening moments of the credit sequence set the heart of the matter right before us and do the productive work of overlaying moving images of the family with a terribly confounding tone—an obfuscating mixture of grief relieved by the jumpy playfulness of the catchy country beat (“Act Naturally,” sung by country musician Buck Owens) and the optimistic prospects that the song’s lyrics foretell: that acting can bring just about anything into being. The play in the lyrics is on the word “act,” the double sense of which is deployed by the tune and, as the film proceeds, is brought into relief. When subjects behave, even when they aren’t playing a role, when they quite simply are, they are in a sense acting—or we might say choreographed—not so much from without but rather moved and motivated from a script inscribed psychically, from within. I act, that is, with respect to my attachment to the modes of being that make me who I am. For I am—like the sons in the film—“condemned to reenact that love unconsciously,” as if choreographed by another. But the thing is, it just comes naturally.

*Eve Meltzer* is Associate Professor of Visual Studies and Visual Culture at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study and an affiliated faculty member in the Department of Art History. Her research and teaching interests are in the areas of contemporary art history and criticism; the history and theory of photography; material culture; and a range of philosophical and theoretical discourses including psychoanalysis, structuralism, phenomenology, and affect theory.

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

The credits and opening sequence for the documentary Capturing the Friedmans can be viewed here. →

1 Lauren Berlant, “Cruel Optimism,” The Affect Theory Reader, eds. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010) 93–116.

2 Judith Butler, “Introduction,” in The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997) 1–30.

3 Ibid., 8.

4 Jean Laplanche, Life and Death in Psychoanalysis (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

5 Ibid., 28.

6 Ibid., 8.