Event

New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collections of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY

Event

New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collections of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY

(Temporary) Collection of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY: Cori Kresge

Cori Kresge, exercise as part of “New Museum Seminars: (Temporary) Collection of Ideas,” 2015. Image: Travis Chamberlain

Dancer Cori Kresge shares her perspective on the term “choreography” in the fifth of seven successive contributions from artists, choreographers, curators, dancers, and scholars for the Six Degrees series “(Temporary) Collection of Ideas around CHOREOGRAPHY.” As part of a daylong symposium in February initiated by the R&D Seminar participants, Kresge presented a short talk and exercise wherein she explored choreography vis-à-vis her own work. The participants of the Seminars asked Kresge to develop her public presentation in tandem with this short text.

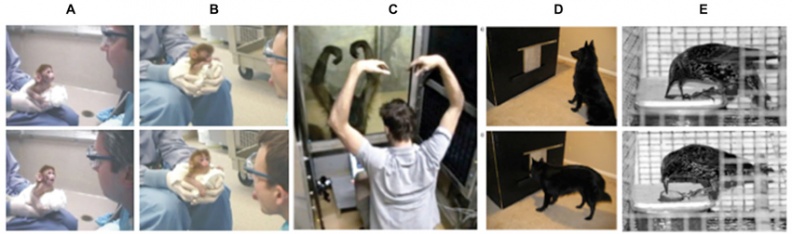

Illustration in Evan W. Carr and Piotr Winkielman, “When mirroring is both simple and ‘smart’: how mimicry can be embodied, adaptive, and non-representational” in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8, 2014

Illustration in Evan W. Carr and Piotr Winkielman, “When mirroring is both simple and ‘smart’: how mimicry can be embodied, adaptive, and non-representational” in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8, 2014

For her contribution to the symposium, Kresge spoke briefly about how, from the perspective of a freelance dancer working daily with choreographers, trust comes into play in the creation of artworks. Citing trust as a reoccurring consideration for her—both as a “meta-human issue” and concern seated specifically within the practice of dance—she spoke about how a social and communal trust must be built within a work in order for an audience to want to engage with it. Kresge articulated how this trust is built in relationships between choreographer and dancer, dancer and dancer, dancer and audience, and body and body before offering the practice of imitation in dance as a way to consider how trust can be constituted between humans. Inviting members of the audience to join her in an exercise where they would practice mirroring without deciding who was leading or following, the movement that ensued further illuminated how trust might come to bear within group behavior. Below are some reflections around the construction of trust from Kresge and a short clip of the group activity that she organized.

TRUST

What is the role that trust plays within the experience of art and movement?

How essential is establishing and maintaining trust throughout the life of any choreographic work, from its inspiration to its production?

These questions recur for me as a student, teacher, performer, creator, and observer of dance. For all involved, the presence of trust is critical to the momentum and “success” of a creative endeavor. If choreography were a car, trust might be the gas in the tank: without it, things slow down, movement arrests, and the people inside get out and walk away…

Art that asks us to enter into places that are new, surreal, or even simulated draws upon the profound delicacy of persuasion inherent in the social creation of dance. In considering what factors create a supportive environment for more trust, it is not necessarily how unpredictable or outlandish an idea or situation is that makes it harder for one to want to follow it; it is whether or not it is supported by its own atmosphere of willingness and commitment.

Having worked with a variety of artists in recent years as a freelance dancer, I often sign a spiritual contract to, as much as possible, trust the choreographer—to not do so might infect the atmosphere around and within the artwork with resistance. The fullest potential of dance cannot be realized without granting everyone’s trust.

Paying more attention to the various ways we, as artists, might build, sustain, and enable trust ethically within a work would have effects that would then ripple out through the world at large. This might be achieved by trusting in our creative instincts, trusting that we will arrive at a new and interesting destination, or trusting that the repercussions of art¬-making will extend into unknowable territories with meaningful impacts. These questions have proved generative for me in past group work:

Allowing for your own personal aesthetic preferences, what might a recipe for building trust with others be?

Tracking your own momentum in movement, what have you noticed causes the most stimulation or stagnation, internally or externally, in your work/play?

What tools do you employ as artists to negate or transform doubts within yourself and your creative community?

Do you think an audience has any responsibility to come to viewing an artwork with a conscious intention of trust?

Cori Kresge is a New York City–based dancer and writer. She was a member of the Merce Cunningham Repertory Understudy Group and part of the Cunningham teaching faculty. Kresge currently works with Ellen Cornfield, Rebecca Lazier, Rashaun Mitchell, Wendy Osserman, Silas Reiner, and Sarah Skaggs, as well as with performance artist Liz Magic Laser and filmmaker Zuzka Kurtz. As a performer, creator, teacher, and viewer of movement, she is currently attracted to themes of trust, commitment, and energetic focus.

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

In 2014, Kresge performed in artist Liz Magic Laser’s piece Like You, commissioned for “Le Mouvement,” a three-part series of performances that comprised the twelfth iteration of the Swiss Sculpture Exhibition in Biel/Bienne, Switzerland. In this performance Kresge intervened in the gestures and patterns that comprise the everyday movements of people throughout the city. For six hours daily from August 26 through August 30, Kresge performed Laser’s work. She was given a choreographic imperative by Laser to develop and carry out a method for mimicking the pedestrian gestures of the passersby in her vicinity. Sometimes reenacting movements from earlier observations, while, in other instances, mirroring the specific gestures or attitudes of those in motion around her, Kresge became involved in a process of choreographic feedback with pedestrians—their movements changing in response to her mimicry.

Documentation of Like You, in addition to a link to the exhibition catalogue, can be viewed here. →

As part of the New Museum Seminars CHOREOGRAPHY semester last fall, artist and dancer Todd McQuade led an exercise entitled “Coordinating, Mirroring, A Rotating Front, and Land-Marks” that addressed mirroring and was centered on the choreographic practices of social behavior. The excerpt below details McQuade’s exercise, which is sourced from the syllabus and bibliography created by the participants in the CHOREOGRAPHY New Museum Seminars. The entirety of the coauthored syllabus can be viewed here. →

As a method of investigating choreography as various ways of “writing the body,” I propose a practical encounter with body languages. Instead of reading a written text, I will direct the group through four physical practices, which call upon different functions of body language. Central to this investigation will be the question of how these practices are located between seeing and doing, feeling and affecting, leading and following, and indicating and nuancing produced subjects—or, rather, how these practices write the choreography of social behavior.

In place of a set of readings, I offer the following set of movements that I will lead the group through. This set is also a discursive framework that others can use in a group movement exercise. Experienced as a sequence, these practices aim to take individuals and groups through an encounter with processes of negotiation of the individual (coordinating), the couple (mirroring), the collectivity (a rotating front), and the body-politic (land-marks).

Coordinating

A person’s physiological coordinations related to voluntary and involuntary physical processes such as locomotion, respiration, and tasking are considered, as well as symmetrical/asymmetrical and hybrid expressive patterns.

Mirroring

Two people mirror each other’s movements. Neither person leads exclusively. Neither person follows exclusively.

A Rotating Front

A group of people follow the movements of the person who is in the center of their field of vision.

As the bodies reorient themselves based on their movements, the determination of who the leader is changes and must be adapted to in the movement of the followers.

Anyone can be the designated leader; this position can change at any time.

Land-marks

“Marks” are correlated with forms of accountability, “land” is correlated with the content of interest/agency.

A score of marks indicating times of arrival/departure, locations in a space, and relationships between individuals is predetermined.

Determination of the score is made either by a subject outside of the acting participants or by the collectivity of the participants.

Each participant begins at a mark and is free to embody their interests in the land between these marks as they progress along the trajectory of the score.