Featured Six Degrees Post

Indexing Liveness: The (In)Animacy of Performance

by Lauren Bakst, R&D Season Fellow

Featured Six Degrees Post

Indexing Liveness: The (In)Animacy of Performance

by Lauren Bakst, R&D Season Fellow

SHOP TALK: Archiving Performance: Terms of Submission with a canary torsi

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum. Archivists from left: Tim Rovinelli, Stephan Moore, Suzanne Thorpe (flute), Caroline Park, Peter Bussigel. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

As residents of last fall’s R&D Season “Performance Archiving Performance,” a canary torsi—a group led by Yanira Castro whose work is anchored in performance—completed the archive of their project “The People to Come: A Participatory Performance Project” (“TPtC”; 2012–13) through a live installation and open studio in the New Museum Theater. During a five-day period, videos of fifty dances, over one hundred audience submissions, and fifty musical scores were edited, catalogued, and uploaded onto the project’s website by the company’s archivists. The website for “TPtC” is an archive of material created by participants—documentation of dances, musical scores, and audience submissions—and the ways in which they were connected.

As part of the “Shop Talk: Archiving Performance” conversation series, which considers methods for archiving and documenting performance or other live art at the Museum in consultation with artists, Travis Chamberlain, Associate Curator of Performance and Manager of Public Programs, and Tara Hart, Digital Archivist, talk with Yanira Castro, a canary torsi Director and Choreographer, and her collaborator, Installation Designer Kathy Couch. They discuss how the archive for “TPtC” was conceived as an integral component of the performances themselves, addressing questions surrounding authorship, ephemerality, and liveness in relation to the creation, presentation, and reception of works of performance. They also ground broader ontological questions of the archive in a discussion of the New Museum’s documentation practices and the Museum’s Digital Archive.

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at the Invisible Dog Art Center. Performers: Simon Courchel, Darrin Wright. Foreground musicians: Stephan Moore, Caroline Park. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at the Invisible Dog Art Center. Performers: Simon Courchel, Darrin Wright. Foreground musicians: Stephan Moore, Caroline Park. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Tara Hart: Yanira, in your artist statement for “The People to Come,” you have written that the participatory nature of your work “challenges ideas of authorship.” If authorship encompasses more than one person and is not static throughout a performance, how does archival description (encompassing various methods for describing archives and their provenance, such as cataloging) function in “TPtC” to represent multiple creators of a work?

a canary torsi (Yanira Castro and Kathy Couch): Parsing authorship was a primary concern in “TPtC.” In the system we set up, we tried to make all of the people and actions involved in the making of a single dance as clear as possible, both in the physical archive space that was generated during each performance and in the online archive. In the performance installation of “TPtC,” one could follow an inspiration around the room. For example, if someone in the audience created a work in response to the portrait prompt (the prompts were to create a portrait, pattern, or task), a member of our team, acting as the on-site archivist, would label the work with the prompt type, name of maker, and its title. They would then scan it for the online archive, catalogue it under “portrait,” as well as put it up on the “submissions wall” in the portrait category. Dancers selected from these submissions for their scores and then taped their selections to the “performer boards” (slabs in the rehearsal space). These boards were put back up in the physical archive after rehearsal and exhibited during the performance. Every single submission in the archive could be followed from its initial creation to its final use. In other words, the processing of a submission into the choreography of a performance happened simultaneous to the performance being translated into a record for the archive. Audiences could see, as the performer was working, the inspiration and the multiple uses of a submission. Tagging functioned on the online archive to produce a web of relations that attempted to disclose authorship, where every dance is linked to the submissions that inspired it and each submission is linked to the dances that were made from it.

In the online archive, we tried to give the work of all creators equal standing by designing three sections under the “Explore” tab: audience member submissions, video documentation of dances, and sound scores. Our hope is that by archiving and then making navigable all the components that went into creating a dance (and ultimately, the event and archive), we are foregrounding connections between multiple authors: the dancers who created the dances, the audience members who shaped it with their inspiration, as well as the collaborators who choreographed or created the situation (i.e., the archivists, installation designer, composer, and director).

Travis Chamberlain: The matter of authorship touches on questions around issues of copyright and licensing of materials, particularly as they apply to archives. In “TPtC,” the contributing audience members are identified as being coauthors of the project. You also ask for appropriate credit lines in order to credit the submissions. However, to submit to the project, participants had to agree to the Terms of Submission, which is a pretty standard release that includes the following statement: “We may use your content in any way.”

By asking participants, that you deem collaborators, to sign away rights (via copyright), does this perhaps allude to levels of hierarchy within the project (i.e., that there are primary authors)? Do you account for this in the archive, say by crediting the various collaborators that comprise the core team of dancers, directors, etc., in different ways?

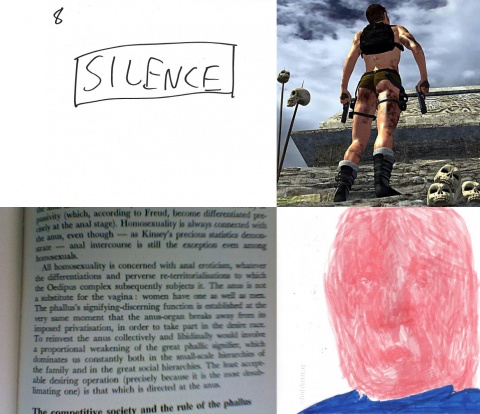

Audience submissions, from left: “Audience Task #18,” task by Stephan; “Tomb Raider,” portrait by Larry Croft; “I lost my keys,” portrait by Hannah; “Guy Hocquenghem, Homosexual Desire. Villiers Publications Ltd., 1978. pp.8,” task by JDR.

Audience submissions, from left: “Audience Task #18,” task by Stephan; “Tomb Raider,” portrait by Larry Croft; “I lost my keys,” portrait by Hannah; “Guy Hocquenghem, Homosexual Desire. Villiers Publications Ltd., 1978. pp.8,” task by JDR.

YC: This topic is so involved that it could be a separate interview in and of itself! It requires teasing out the meaning of the term “collaborator,” looking at the various types of relationships between individuals and organizations, examining how crediting functions in artworks, and whether copyright can ensure control over how an artwork is used and remuneration for its use, etc.

The Terms of Submission wasn’t given very serious consideration—we had no one legally knowledgeable about copyright on the team nor could we afford to hire a lawyer. We simply took, verbatim, the terms from another interactive website that asks people to submit creative materials: dearphotograph.com. Our major concerns in making an agreement were that someone might claim someone else’s work as their own. And we wanted people to be aware that once a submission was entered, anything was fair game. We would not control the context around how a submission might be used by a performer.

In regards to hierarchies within “TPtC,” the level of investment of time, capital, visibility, etc., was very complex. How to measure and reflect this? We did not pretend to work in a system where these different investments did not matter and all was equal. As we see it, there are levels of hierarchy at play at any given moment in a project. Furthermore, hierarchy does not preclude collaboration—they are two different things (i.e., a collaborative system could be highly vertical or more horizontal). From our perspective, “TPtC” is a collaborative project that attempted to be as inclusive as possible while acknowledging the fact that certain people enabled and shaped the project in different ways (mainly the core collaborators who conceived of the structure together).

The core collaborators assumed that there would be no net financial income from the project. From the onset, we worked from the expectation that all involved were makers contributing to a project that would have no funds to disburse beyond commissions and tour fees, so we never tackled that issue. Had a situation like royalties existed, it would have brought up issues not just of crediting, but of appropriate compensation to all authors (given different levels of time, capital, etc.). In regards to public attribution of material to their makers (or accumulation of creative capital versus financial), we required anyone submitting material to give us a name for crediting purposes. Of course, the name they used was entirely up to them and some people submitted anonymously or used a pseudonym. It is important to note that, as the director, I tried not to give any submission priority over another; their use was solely at the discretion of each performer.

TH: This discussion on authorship speaks directly to how the principle of provenance in archives continues to be reconsidered and redefined to account for participatory, self-organized models forged by artists and art collectives, as well as the development of new media and the proliferation of born-digital materials. For example, an archival “document” today is not limited to text fixed on paper, but can encompass multiple formats and media types (including analog, digital, and para-digital). Archives have been traditionally defined as materials created or received by an individual or organization in the conduct of their affairs, and are kept because of their long-term value (for research or other aims), but an archive (or archives) can also mean an organization (or division within an organization) that collects these materials.

The New Museum’s Digital Archive was developed with the aim of providing ongoing documentation of the institution’s activities and ideas. With the focus on creating a platform for research that is continually expanding, we are particularly concerned with providing access to archival traces of art practices that might resist traditional museological modes of documentation, such as dance or performance. An artist’s engagement with the Museum occurs in multiple stages, from conception, to rehearsal, to performance, or live event, and we are still wrapping our heads around how to provide access to documentation and archival material that sheds light on the intricacies of each step.

In performances of “TPtC,” the rehearsal process and the live presentation of the solo piece are allotted a temporal structure, of nineteen minutes each. Is this equivalent allocation of time an indication that the process involved in the conception of a dance is just as valuable as the performed work? Is it possible for audiences to understand individual performances within “TPtC” without an understanding of the rehearsal?

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at the Invisible Dog Art Center with Luke Miller and submissions wall in background. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at the Invisible Dog Art Center with Luke Miller and submissions wall in background. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance Simon Courchel and Darrin Wright. Photo: David Bivins

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance Simon Courchel and Darrin Wright. Photo: David Bivins

YC & KC: Yes, the amount of time we set for these two elements was an indication that process and product are equal. Consequently, the time performers had to research submissions in the archive was the same duration—in other words, not only was the rehearsal and the performance given the same weight, so was the research.

We made a practical decision to show only “final” works online, such as performances, submissions, or musical scores. Logistically, we could not document the process of each submission’s creation or how the hundred-plus musical scores were made, so we decided to not include rehearsal footage either. This does not mean, however, that there isn’t evidence of the process of how the dances were made. For example, many of the audience submissions bear the marks of use from the rehearsal process by the dancers. Also, the submission cards were often created onsite in response to a dancer’s request, a performer’s solo, the structure of the event, or were portraits of audience members.

When considering how to utilize the online medium to best challenge and trace lines of authorship, we emphasized recording the connections between the components that went into making each solo dance, not the entirety of the process that created it. It is not the dances themselves or the submissions that are, for us, as important as the cumulative web of connections—the online archive visualizes and displays these connections, serving as a portrait of the overall project.

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum with archivist, Kirsten Schnittker. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum with archivist, Kirsten Schnittker. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

TH: The online archive produces its own experience for online audience that is distinct from the individual live performances. Did you previously work with analog forms in documenting a canary torsi’s work, or has documentation primarily been both digital and online? How do you feel the progression of digital technology and its attendant ability to present work to an online audience impacts the conception and understanding of your work?

YC: Prior to “TPtC,” documentation of my work has been primarily in video and photographs, housed on my website or on my Vimeo account. Having online documentation has certainly made it easier to “share” work. It is, however, problematic if this is understood as the work itself or approximating the total experience. Since 2007, a canary torsi’s work has been primarily about the explicit relationship between audience and performance, and that relationship dramatically impacts what unfolds in the physical performance. Therefore, each performance is not only different from the next (i.e., there is no “definitive” performance to capture), but the ability to record video is also often impossible without disrupting the performance.

As you said, the online archive offers a completely different experience to a web audience. We hope that it inspires activity more than simple video documentation by giving context through the connecting material. Video is deadening to live work—it needs to be contextualized, with the recognition that the liveness of performance does not transfer to a digital image. Consequently, digital technology might be able to elucidate webs of relationships that are not inherently visible in video documentation.

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum with Director Yanira Castro. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum with Director Yanira Castro. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

TH: As an archivist who works to select and contextualize large groups of archival records (born digital as well as analog), I appreciate the amount of time it takes to tend to archives related to performance. Some key debates in performance studies have explored the relationship between liveness and mediatization. Twenty years ago, Peggy Phelan famously argued that “Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance.”1 Writing on liveness in 1999, Philip Auslander claimed that Phelan’s ontology yielded “a reductive binary opposition of the live and the mediatized,” arguing that performance can only exist within the present economy of reproduction.2 More recently, scholars such as Rebecca Schneider have asked, “If we think of the ephemeral as that which ‘vanishes,’ and if we think of performance as the antithesis of preservation, do we limit ourselves to an understanding of performance predetermined by a cultural habituation to the patrilineal, West-identified logic of the archive?”3

Amongst those working within the overlapping communities of contemporary dance, poetry, and digital art, the term “liveness” can have different meanings. Can you tell me more about how you came to your particular understanding of liveness?

YC: How a performance functions in any given moment is slippery—its production and reception is a messy web of connections that are impossible to fully parse. Personally, when I see a performance everything is at play: my past experiences with the artists involved in the project; articles I’ve read about the artwork; other pieces I’ve seen by that artist or related media, such as materials from websites, photographs, etc. I am not a purist—to pretend there is pure interaction with performance (or any art form) is ludicrous. These various mediated engagements make up my personal set of interconnected experiences with the artwork in real time. I take issue with the concept that performance be given some special place of existing solely in the “now” (you could call this a fetishization or romanticism of the potential of the form above other forms or media). In this respect, I suppose I stand with Auslander.

I understand liveness as having at least three distinct elements, all in constant relation to one another and shaping experience in multiple ways. First, there is the person who is engaging with the artwork: the perceiver, or participant, or witness. That person is having multiple experiences, and it is impossible to record all of them at any given moment. Second is the art event or object—it can be “static” or “live.” A static artwork would be, say, a painting, in that the artwork does not change; a “live” artwork can vary greatly, from the dance that is set to music and has a singular ideal outcome, to a whole range of works from improvisation to participatory installations, etc. The third element is the shifting environment of reception—the light, behavior of other audience members, smells, level of heat, etc. Beyond that, there are the cultural, political, ideological, and social contexts. As I said, it is messy.

Documentation is another element in the web of interactions, which is distinct from the live event (although connected in that it is a residue or imprint of it). In relation to “TPtC” as a whole, the website, videos, cards, documentation, etc., are all an extension of the project—artifacts and art projects themselves. The live event vanishes and its trace largely remains in memory. The record is not the performance or the representation of the live event—it is not a substitute. For me, its function is akin to memory.

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

a canary torsi, “The People to Come,” 2012–13. Performance at New Museum. Photo: Travis Chamberlain

TC: a canary torsi’s “TPtC” has had an important impact on my understanding of the relationship between performance and archives, and how they can function together as a modifiable system. Within such a system, as it might be applied to the context of the New Museum, the live event is no longer the culmination of the Museum’s engagement with an artwork, but part of a longer process that exceeds this. It is worth considering, however, that the performances in “TPtC” were made to fit the machinery of a particular archiving system that a canary torsi created. The Museum’s Digital Archive is also a system—though we cannot expect all performance to perfectly fit our system, any more than one would expect all performance to fit that of “TPtC.” Considering this, we are presently rethinking the ways in which we can collaborate with artists to produce the most relevant documentation possible with our resources, and then how this documentation and other traces (beyond straight video or photo recordings) might be entered into the New Museum’s Digital Archive as an “artist-authorized record” alongside institutionally selected materials. If an artist understands what a processed record in the Museum’s Digital Archive is, how it is classified, and how it might be used, then the artist can help us to produce records that best utilize this structure to, in their opinion, most suitably represent their work.

In the second part of this conversation coming at the end of July, a canary torsi asks Chamberlain and Hart questions related to the representation of performance’s liveness through documentation at the Museum, paying particular attention to the way in which records of performance are presented online through organizational structures and taxonomic systems. Questions about the Museum’s responsibility to document performance, and how this can relate to forms of audience engagement, are addressed in relation to recent public programming.

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

This video shows two performers (Luke Miller and Peter Musante) and audience members using “TPtC” archive. Alongside the audience members browsing and creating new submissions, some of the archivists who oversaw the space and processed the submissions can also be seen at work here. →

The Society of American Archivists (SAA), a professional association for archivists, put together a glossary of terms, entitled A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology. Published in 2005, the glossary contains more than two thousand entries based primarily on archival literature in the United States and Canada. To look at how terminology, from “cataloging” and “record,” to “corroboration” and “destruction,” has been defined by a group of practicing archivists, download the full PDF here. →

1 Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 146–66.

2 Phillip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), 3.

3 Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 91.