Exhibition

Temporary Center for Translation

Exhibition

Temporary Center for Translation

Six Degrees Residency: Para-sites like us

Implicated Theatre, Theatre of the Oppressed, 2012. Performance: Migrants Resource Centre, London

“Para-sites like us” is an ongoing research project initiated by Janna Graham, the inaugural Six Degrees resident. Graham’s series of texts examines the para-sitical condition as a potential coordinated political struggle, one that might make “good on culture’s claim to social transformation” by working para (i.e., alongside), within, and as other to institutions.

PARA-SITES LIKE US

In many mainstream cultural institutions a dichotomy exists between those attempting to make good on culture’s claim to catalyze social transformation from below and those who make use of these claims to build networks based on hegemonies of taste, class, and education from above. Far from the heroic position of the historical avant-garde, these critical agents,—whether they be institutionally named as artists, curators, educators, or ”community partners,” often understand themselves to be “para-sites” or as engaged in acts of “para-siting.” By this, they/we refer to the act of attaching oneself to hegemonic (or, at the very least, deeply conflicted) hosts, attempting to make good on critical and socially transformative narratives of art and the public—and on the philanthropic dollars that have been attributed to them—in environments that may speak to these same goals but operate in fundamental contradiction. The para-site occupies a terrain that is both inside and out and that is very often located in the shadowy greys, placing its body in hegemonic infrastructures with desires and accountabilities that exist in parallel, in other sites, and in the name of social justice.

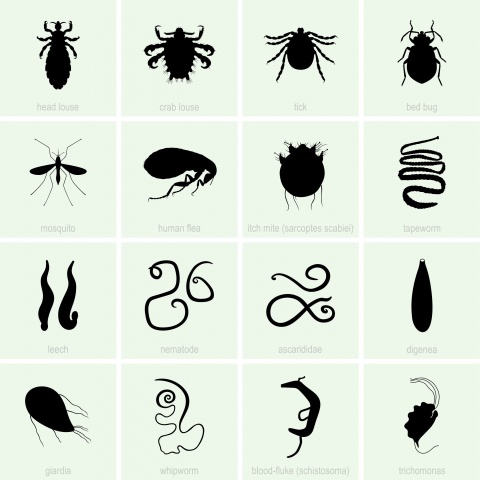

Illustration of a set of various types of parasitic organisms that are dependent on human bodies for nutrients. © barbulat

Illustration of a set of various types of parasitic organisms that are dependent on human bodies for nutrients. © barbulat

In its wider connotation, the parasite is a recurrent social trope, often understood in derogatory terms, referring to those who are thought to have no right to feed off of society’s wealth, as though that wealth were not created at the hands of exploitation. As a lived condition and not an idealized political narrative, the para-site’s capacities for change depend on its specific actions and impacts. As a figure for contemplation, the parasite, in both its human and microbial manifestations, is significant for its multiple potentials: to exist in benign silence, to multiply or to irritate, to usurp resources or to completely take over its host, or to have the latter do the same.

The problematics and complicities of the para-sitic condition have been well circulated: through the ways in which governments, cultural institutions, and corporations instrumentalize art’s critical and socially-oriented agents and programs to positively image corruption, to tame unruly bodies, to valorize precarity, and to de-house neighbors deemed uncreative.1

Its virtues are equally volleyed about: In the litany of “Art AND…” exhibition titles, ever-new kinds of “aesthetics,” and ever more content spectacles dedicated to individualized practices of art, revolution, social change, and social practice and its histories.

Less has been said about the para-site as a serious—albeit ambivalent—organizing political force within and outside of the cultural field. Even fewer individuals have analyzed its capacity to infect, irritate, or alter its host, or the efficacy of its attachment in achieving social and political goals. As such, little work has taken place to evaluate whether the transversal collectivities, alliances, and accountabilities produced by para-sitic activities are politically useful to the projects of social justice to which they orient themselves and are indeed committed. These conversations—about use, about accountability, about the political work of para-sites—often take place in whispers at the edges of projects and in the million details through which the overlay of critical cultural work and the mechanics of their hegemonic host organizations is experienced, but seldomly in the discourse that surrounds them.

As a result of this omission, the commitments and genealogies that are at the heart of the para-sitic work are often obscured, and their contribution to the projects of social justice missed. Accounts of them rarely address the political successes or failures of their practices vis-à-vis the hybrid political questions at stake. And the polyvocal transversal groups that constitute and are constituents of para-sitic work are generally silent as narrations are called for by artists, curators, educators, and directors and oriented towards funding bodies and others within the profession. Questions of complicity, form, and efficacy are rather presented as through questions for and within the world of art and not for those who are affected by the attempts of its agents. These accounts, though often unwittingly, affirm the verticality of the hegemonic institutions they claim to detest and perpetuate further the work of art’s liberal and individualizing tendencies. They also hold us back from distinguishing between what is a para-sitic practice and what is a practice that affirms the status quo—or, for example, distinguishing between what is a “social practice” and what is a practice of social justice.

This series marks the beginning of a project inspired by my experiences of working collectively with artists, community activists, friends, and colleagues, and our regular disappointment with the distance between narratives of and potentials for social change in the art world and the contradictory reality experienced living among its conditions. It is not research so much as it is a reflection on what we might learn from both the disappointment and the possibilities these collective processes have opened up. As most of these reflections are based on the collective work, I do not lay claim to them as my own but those of emerging processes.

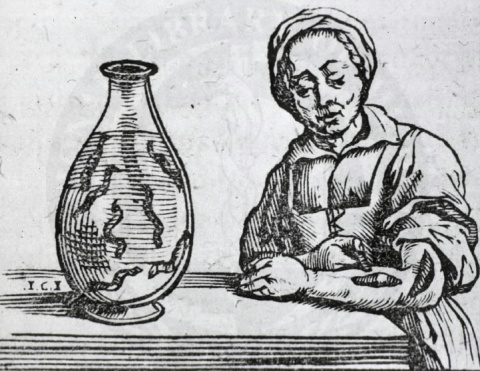

Woodcut illustration of a woman using leeches in bloodletting, from Guilelmus van den Bossche and Christoph Jegher, Historia medica, in qua libris IV. animalium natura, et eorum medica utilitas esacte & luculenter (Brussels: Typis Ioannis Mommarti, 1639)

Woodcut illustration of a woman using leeches in bloodletting, from Guilelmus van den Bossche and Christoph Jegher, Historia medica, in qua libris IV. animalium natura, et eorum medica utilitas esacte & luculenter (Brussels: Typis Ioannis Mommarti, 1639)

Some questions that underpin the series include:

How do we think our way to the institutions of culture from the para-sitic projects of social justice that sometimes encounter them?

What is the genealogy of the para-site? Why do critical agents work in hegemonic cultural institutions? When have social movements made use of these institutions? What parallels might be found in other fields?

What does it mean to think about para-sitic projects from the constituencies they produce: from the transversal groups they create and through the terms and accountabilities of the political struggle with which they are engaged?

Who is winning in the tangle between para-sites and hosts: Is it at all possible for cultural institutions to support grassroots work without distracting from, hierarchizing, or territorializing it? Do para-sitic agents have to change their hosts or is it more important that the host simply support social struggle, knowingly or not?

Are there any advantages of being a para-site in this particular moment in history or are there other strategies that would serve the work of social justice better?

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

Below are a few examples of projects and texts that depart from the parasite as a recurrent social trope in the field of the arts.

Operative in New York City from 1997 to 1999, according to literature distributed by the group, Parasite was “an artist-run organization formed to support, document, and present project-based artwork. As a secondary (or para) site for projects undertaken at other locations, Parasite aim[ed] to develop a discursive context through activities within occupied ‘host’ organizations.”

Coming out of artist Andrea Fraser and critic and curator Helmut Draxler’s project “Services: The Conditions and Relations of Service Provision in Contemporary Project Oriented Artistic Practice,” (1994–97), a traveling exhibition that developed around a series of working group discussions and collective research endeavors that attempted to address the conditions for display, reception, and consumption of artworks and artistic practice, Parasite focused on “project-based artwork” and the complex relation this type of work has to arts institutions. Between 1997 and 1999, Parasite—which included artists Dennis Balk, Andrea Fraser, Renée Green, Ben Kinmont, Christian Marclay, Florian Zeyfang, and others—organized a series of meetings, public presentations, and exhibitions at New York arts institutions, including the Clocktower Gallery and the Drawing Center.

Parasite examined various roles (artist, curator, critic, historian, etc.) and contexts in the production of art discourse and history. For example, at the Drawing Center in 1998 the group presented artist Mel Bochner’s “Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to be Viewed as Art” (School of Visual Arts, 1966) through a series of binders that collected photocopies of Bochner’s drawings and working materials on white pedestals alongside various textual materials produced around the artwork, including an essay by James Meyer about the original 1966 exhibition held at the School of Visual Arts Gallery and a short interview with Bochner by some of the group’s members.

An archive of documents related to Parasite’s activities is housed at New York University’s Fales Library and Special Collections. You can view a finding aid for the collection of documents and materials here. →

Several images of the project can be viewed on artist Nils Norman’s website here. →

Read an account of the exhibition in 1998 at the Drawing Center, originally posted on nettime on March 23, 1998 by unknown user, on artnetweb here. →

Artist Michael Rakowitz introduced his social practice art project “paraSITE” (1997–ongoing) in the exhibition catalogue for “SAFE: Design Takes on Risk” (2005–06) at MoMA by describing what he saw as the fundamental nature of the parasitical relationship: “Parasitism is described as a relationship in which a parasite temporarily or permanently exploits the energy of a host.” This language framed the temporary and transportable shelters he designed from Ziploc and garbage bags that were given out, free of charge, to numerous homeless people in several East Coast cities starting in 1998. Dependent on the warm air coming from outtake ducts of buildings’ heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems (HVAC), these double-membrane structures rely on attachment to a host building for their form and source of heat. Rather than provide a large-scale architectural solution, these hand-crafted structures primarily draw attention to the systemic conditions of homelessness. Through a custom and collaborative design process which accounts for each homeless person as an individual human with specific needs, Rakowitz tackles the failures of representation in addressing homelessness in American society by redirecting the surplus of a host in order to provide basic housing for those who have none.

A video of the one of the structures being set up can be viewed here. →

Various accounts and photographic evidence of each iteration, custom-designed for each individual user, along with the back story of how this project came to be can be viewed in a post on the Worldchanging blog here. →

In “A Productive Irritant: Parasitical Inhabitations in Contemporary Art” published in Fillip (Issue 15, Fall 2011), the curators Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick approach the parasitical in the cultural realm through the lens of artistic strategies. The article begins with a breakdown of French philosopher and author Michel Serres’s The Parasite (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982) and an account of how his definition of the parasite is shaped by three commonly held perspectives of the term, as biological, social, and communicative (since “parasite” is also the French word for noise). Serres addresses the concept’s appearance in literature and science, drawing from the fields of sociology, biology, and information theory to examine how systems operate. The authors depart from Serres’s text which “discusses its namesake as a vehicle for introducing ‘irritants’ to any given order, causing subtle changes that can be productive and cumulative” to examine, “certain artists’ parasitical operations as effective strategies for the manipulation of context, the introduction of unsuspected tactics, the identification of weakness within seemingly taut and enclosed systems…” Going on to look at the parasitical strategy as not merely antagonistic but also productive, they examine case studies ranging from the artwork of Harvey Stromberg, the Yes Men, BANK, Adrian Piper, and many others that parasitically feeds off of the funding, organizational structure, habits, sites, and history of hosting arts institutions.

Read the article in full here. →

1 Some recent examples of the discourse around the problematics and complicities of the para-sitic condition include Liberate Tate’s investigation of how contemporary art is used to whitewash oil sponsorship <https://liberatetate.wordpress.com/> (accessed Nov. 14, 2014); theorist Brian Holmes’s critique in “Liar’s Poker: Representation of Politics/Politics of Representation” Springerin 1 (2003), <http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=1276&lang=en> (accessed Nov. 14, 2014); Southwark Notes’s writings on how artists are interpolated into the development process <http://southwarknotes.wordpress.com/art-and-regeneration/> (accessed Nov. 14, 2014); and Precarious Workers Brigade’s Photo Romance <http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/page/2> (accessed Nov. 14, 2014).