Exhibition

Gerard & Kelly: P.O.L.E. (People, Objects, Language, Exchange)

Exhibition

Gerard & Kelly: P.O.L.E. (People, Objects, Language, Exchange)

On Reverberations

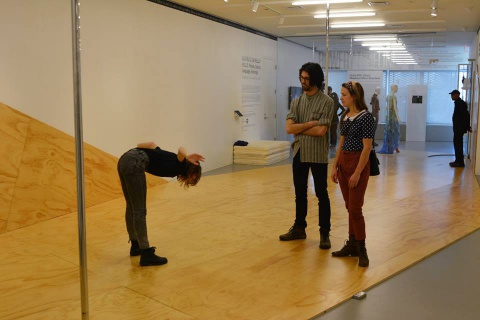

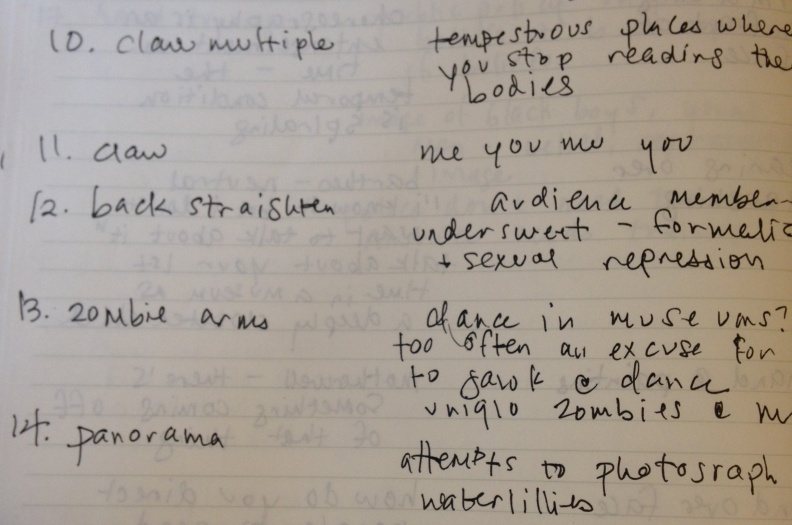

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

Lauren Bakst was the R&D Season Fellow for CHOREOGRAPHY. In a series of three texts published on Six Degrees, Bakst shares several lines of inquiry she pursued while researching the R&D Season’s thematic during her residency, addressing how considerations of subjectivity, affect, memory, and history can be taken up through the skilled dancer’s body and choreographic forms within exhibitionary spaces.

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

During my time as the R&D Season Fellow at the New Museum, one of my primary responsibilities was to document the activities of the CHOREOGRAPHY Season, which included a six-month residency by the artist duo Gerard & Kelly (a collaborative partnership comprising Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly). Their residency consisted of a research project and a subsequent exhibition in the Museum’s galleries, both under the name of “P.O.L.E. (People, Objects, Language, Exchange)”; two series of public programs, “In Bed With…” and “Open Pole”; various workshops run by the artists and CLASSCLASSCLASS; performances of works including Reverberations and Two Brothers; and other artworks that were used, developed, or produced during the residency and cycled in and out of these temporal and physical spaces. A large part of my role as the R&D Season Fellow included researching and documenting all of the activities within the Season. In our conversations at the beginning of their time at the Museum, Brennan, Ryan, and I began discussing with Johanna Burton, Keith Haring Director and Curator of Education and Public Engagement at the Museum—who initiated both the Season and their residency—what form my documentation of the Season’s programming might take. Because of the research- and event-oriented nature of their project “P.O.L.E (People, Objects, Language, Exchange)” and Brennan and Ryan’s interest in the role of the witness and the transmission of memory, more conventional types of documentation didn’t feel like the right approach. Furthermore, as someone working in dance as a performer, an artist, and a writer, I have been interested in how these various modalities of work could come together to inform my temporary position at the Museum. The three of us discussed at length how my roles as a witness and a documentarian might be animated and point to how subjectivity is implicit within forms of documentation. Museum exhibitions are often remembered through a catalogue or publication—we thought, instead: What might a living document of an exhibition look like? Reverberations came out of this inquiry.

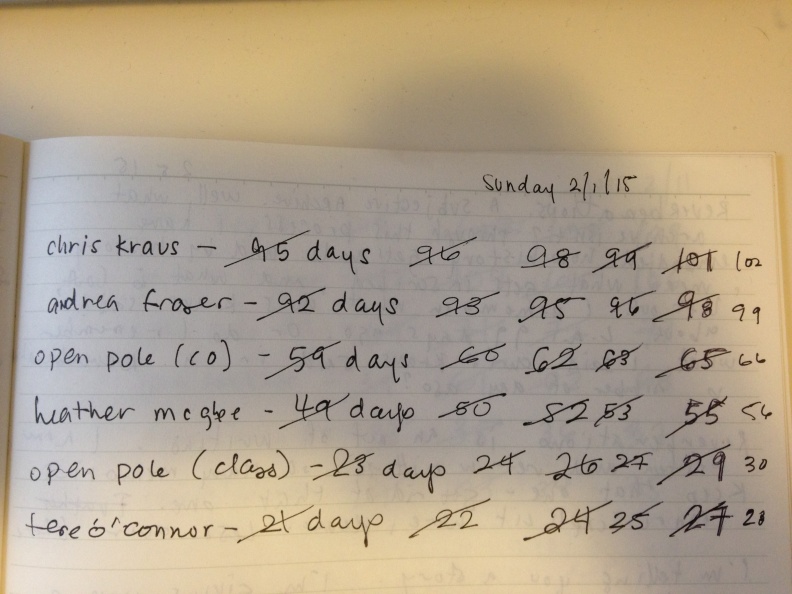

Reverberations is a method for recording, archiving, and transmitting events that have previously taken place. Over the course of Brennan and Ryan’s four-month-long research-oriented installation for “P.O.L.E.” on the Fifth Floor of the Museum, I recorded six events: Four were a part of “In Bed With…,” a series of intimate conversations between the artists and invited guests who were influential in the development of their work—writer and critic Chris Kraus, artist Andrea Fraser, legal scholar and advocate Heather McGhee, and choreographer Tere O’Connor—which took place on mattresses dispersed throughout the gallery and were open to public audiences. The other two events were iterations of “Open Pole,” a series of gatherings organized by Brennan and Ryan around two vertical poles installed in the gallery; they were held during evenings when the Museum stayed open late at a pay-what-you-wish rate and included various outside collaborators who ran movement-based classes, practice sessions, and performances. One “Open Pole” event was hosted by the Chosen Ones, a crew of dancers that typically performs in New York City subways, and the other was a pole dancing class taught by dance and exercise instructor Keisha Franklin. The installation of the two poles in the gallery functioned initially as a conceptual gesture—one that raised questions such as: What happens when the ballet barre is flipped from the horizontal to the vertical? What happens when the pole is a functional tool for movement and also a sculpture? How can an exhibition function as a research platform for the investigation of the politics embedded within dance forms ranging from ballet to pole dancing? These questions were continually animated through the communities of dancers who came to “Open Pole” events, hailing from the worlds of competitive and fitness pole dancing, queer and radical faerie culture, street dance, and contemporary performance.

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

Reverberations consisted of two distinct phases: recording and transmission. (The score was written by Brennan and Ryan and was developed over time through our rehearsals and conversations.) The instructions for recording—as directed by the score in its original form—were as follows:

As researcher, you should attend the event and record what happens. Observe the movements of all participants including members of the public and yourself. Choose around ten movements over the course of the event that pique your interest or strike you as significant. Remember what is being spoken when the movement is produced. Enact and repeat these movements as necessary in real-time to encode the choreography of gestures, movements through space and around the mattress, incidental motions (shrugs, nods, facial reactions, gesticulations of the hands), and postures that you see. Take the movement as choreography; you should encode this so that you can later demonstrate it. Use accumulative modalities to keep the movements in chronological order.

What actually took place as a result of these directives? During the events that I was “recording,” I intently watched, listened, furiously took notes, and, at times, subtly mimicked people’s movements so as to encode them in my body. My primary strategy was to use writing as a form of inscription, employing my own idiosyncratic and descriptive notations of the spoken and the gestural as tools for remembering. Whether I was “recording” a primarily conversational, language-based event like “In Bed With…” or a movement-oriented event like “Open Pole,” I inhabited a choreographic position—making selections about what to remember and what to forget. In rehearsals with Brennan and Ryan to prepare for the subsequent “transmission” phase, I would relay my memories of the given event by performing the series of discreet gestures I had encoded and explaining what was said at the moment of each movement’s original enactment. These physical gestures and the spoken language recalled my specific choreographic recollection of the event—the movements, words, and actions of the participants and audiences as I had perceived and embodied them. It is important to acknowledge the matrix of subjectivity and power at play in this role in which I, a young, able-bodied, middle-class, educated, white cis-woman, performed the role of documentarian-archivist-orator in the work of two white, gay cis-men. Furthermore, my role involved recalling gestures and speech from both older and more educated individuals as well as from a range of performers—mostly cis-women and men of color who occupy socioeconomic statuses that are very different from my own. While these identificatory categories do not fully account for any of our subjectivities, the directional currents of power within Reverberations at times felt exciting and possibly subversive, while at other times the work seemed to unintentionally reify socially embedded flows of information and power.

During rehearsals, Brennan, Ryan, and I would sometimes jointly narrow the selection of memories or refine the language that I would draw from when transmitting during my performances. Reverberations is a subjective archive, with an editorial process full of adaptations, both conscious and unconscious. It is a form of writing history, an embodiment of how events are inscribed, altered, transformed, or lost altogether. As I would repeatedly perform my memories of specific events, I began to wonder if I was conflating what originally occurred with my transmission of what took place. For example, did I really remember what Chris Kraus said during “In Bed With…” about people moving to Los Angeles? Or did I remember what I said she said? Like a childhood story told over and over again, what becomes most important is not the closeness of the story to its original narrative structure and delivery, but how the story comes to matter and carry meaning within the context of a life. As my memories of these events became codified through my own retelling of them, the stories that emerged were those that came to matter within the context of Brennan and Ryan’s project as a whole—those that addressed issues of race and representation, dance and the museum, psychoanalysis and subjectivity, and queer legacies of artistic practice.

Reverberations was developed not only during private rehearsals by myself, Brennan, and Ryan, but it was also transmitted recursively through repeated unannounced performances during public hours within the Fifth Floor installation of “P.O.L.E.” Before enacting the score, I would prepare by writing about each of the events I was about to transmit. This writing would take the form of “I remember…” or “I don’t remember….”

I remember the Chosen Ones. The light fell and broke on his back. They were constantly helping, cheering, supporting, in awe of each other. Were they showing us how to watch them? Were they modeling a kind of system? I remember taking pictures on my iPhone while receiving notifications about the protests taking place. I remember, I remember Chris moving her eyes back and forth. I remember how I move [sic] my eyes back and forth as Chris did.

Pages from Lauren Bakst’s notebook

Pages from Lauren Bakst’s notebook

Pages from Lauren Bakst’s notebook

Pages from Lauren Bakst’s notebook

I would then exit the Fifth Floor offices of the New Museum and walk into the gallery, setting the timer on my phone to mark one hour. For the next hour, I would “reverberate” my memories from a specific event or pair of events for uninitiated Museum visitors and the security guard on duty. While enacting the score, my transmission was always framed by, “An event took place here [X] number of days ago. This is what happened.”

During the four months from October 8, 2014, through January 25, 2015, that their research presentation took place in the Fifth Floor Gallery, Brennan and Ryan were working toward a subsequent two-week exhibition in the Lobby Gallery—also titled “P.O.L.E.”—that would be the culmination of their R&D Season residency. While “P.O.L.E.” was on view in the Lobby Gallery from February 4 through 15, I performed Reverberations for approximately two hours on every day that the Museum was open. By that point, I had accumulated a lexicon of eighty-seven gestures with corresponding memories from six events that took place anywhere from twenty-five to one hundred and two days prior. My transmission of these events could operate in what Brennan and Ryan referred to as two different modalities—speaking and non-speaking. In both modalities, I would perform the gestures from each event in the original chronological order in which they had occurred; while the chronology of each event remained intact, a major function of the score was jumping in time from one event to another by making discursive or gestural connections between memories.

In the non-speaking modality, connections were made through the likeness of one gesture to another. For example, a universal occurrence in every event was that someone took a picture using a smartphone: a thumb touching a screen while standing seventy-six days prior, connected to a thumb touching a screen while kneeling one hundred and two days prior, connected to fingers pulling apart on a screen to focus an image three days prior. In the speaking modality, I could also make connections between discursive content. For instance, a memory from “In Bed With…Andrea Fraser” in which Andrea, Brennan, and Ryan were addressing the potential and the problematic of dance reentering museums at this contemporary moment cued a memory from “In Bed With…Tere O’Connor,” in which an audience member asked Tere how he felt about this very phenomenon. In making this connection, I jumped in time from a one-hundred-and-two-day-old memory to a twenty-five-day-old memory.

In addition to being distinguished by the use or nonuse of speech, each modality also held a specific relationship to the spectator. In the non-speaking modality, I attempted to put myself back in the context of the gesture I was performing—imagining all the details of how and where it was enacted, and by whom. As a result of being preoccupied with the images from my memory, rather than the space I was physically inhabiting, I would not pay attention to the Museum visitors who happened to be in the gallery, and who may or may not have been watching me. Within this modality, I could let the gestures I’d pull from the lexicon move me through the space and shift my direction. When enacting a gesture I played with lingering in or endlessly repeating it. This active choreography created a kind of dance that did not necessarily demand attention. I would always begin a performance session of Reverberations in this modality and would only shift to the speaking modality if I felt that a spectator was actively paying attention to my presence. At that point, I could choose to shift to the speaking modality by approaching and “reverberating” specifically for that spectator, combining the gestures I had previously been enacting with speech. In this modality, I would remain oriented towards, and in close proximity to, that person until one of us decided to leave.

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Video: Danny Carroll

Over the duration of the exhibition I continued to incorporate new memories into this lexicon, drawing upon the actions of the people watching me as well as from the performances of Two Brothers, another score by Brennan and Ryan that took place in the gallery daily. One example of how an encounter with a visitor directly resulted in such recursivity was when, on the second day of the exhibition, a man in a black-and-white checkered sweatshirt touched my arm during the performance. He wrapped his hand around my bicep, almost as though he were checking to see if I were real. I could tell he was excited that I was speaking directly to him. While at first I was disarmed by this and the sense of privilege he must have possessed, enabling him to touch me on a whim as he did, I was ultimately grateful for this awkward and momentary physical encounter. The beauty of Reverberations is that I could choose to take his act and then make it my own. The position of the performer working in a nontheatrical context, in which the relationship between performer and witness is not clearly defined, is a vulnerable one. Having a built-in structure for responding to these relationships and the environment as it unfolded gave me a sense of autonomy as I worked. I looked at my watch to check the time, and, a minute later, I reached out and touched his arm while saying, “An event took place here one minute ago. You touched my arm.” His move became a part of my history, and, as a result of feeding this shared encounter into my singular body, throughout the remaining eight days that I performed I then granted myself permission to touch other people’s arms.

During the time that I performed Reverberations the work was a performance, but it was also a practice that I returned to. In the time leading up to the exhibition of “P.O.L.E.” in the Lobby Gallery, there were moments when I questioned where (and if) I existed inside of the score. I’m telling you a story. I’m giving you a body. But whose story? Whose body? Inside the practice of enacting Reverberations, I came to understand that my subjectivity was revealed through the “what” and “how” of the connections made within and the way I navigated being witnessed by Museum audiences during this process. Within each exchange, I could make decisions to knit information together or place threads of thought side by side and let the person watching fill in the rest. I realized that with this attention and sensitivity to the associative and narrative links between information also came a dramaturgical responsibility to Brennan and Ryan’s exhibition. In the context of the Lobby Gallery presentation of “P.O.L.E.,” Reverberations functioned as a kind of glue, creating a shared discursive context for the other sculptures, videos, and performance work presented in the exhibition.

Under the framework of Reverberations, the dialogue by the invited guests from “In Bed With…” collected like voices in my head—Chris’s subtle undermining of hierarchies of knowledge, Andrea’s precise invoking of a field of relations, Heather’s critical articulation of the relationships between race and public policy and the weight of representation, and Tere’s undeniable wit and positions on the craft of choreography and dance. The discursive ghosts occupying my head from these talks were joined by traces of the ways that bodies organized themselves around poles for the two “Open Pole” events that I also “reverberated” during. In the aforementioned pole dancing class taught by exercise and dance instructor Keisha Franklin, the sociopolitical contradictions embedded within the format of a dance class populated primarily by trained black and queer bodies for a public audience of onlookers was felt. Their movements, at times, broke with and, at other times, maintained the spectacle: for example, the extreme physical labor it took to get up, down, and around the pole; the sense of empowerment and achievement when that labor paid off; and the way this labor was met by the gazes of onlookers.

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

Gerard & Kelly, Reverberations, 2015. Performance: New Museum, New York. Performer: Lauren Bakst. Photo: Danny Carroll

The score that emerged out of Brennan and Ryan’s research into pole dancing was Two Brothers, a score for two performers and two poles. The rotating cast of performers for Two Brothers included TyTy Love, Tyke Turner, and Forty Smooth (three dancers who perform on subways); Tanya St. Louis and Roz “the Diva” Mays (who hail from competitive pole dancing and fitness contexts); and Justin Tate (who comes from a contemporary art background). Two Brothers held a very different kind of time and attention than Reverberations. Whereas Reverberations lived in the space of the nonevent, Two Brothers was a clearly defined focal point of the exhibition’s culmination. For example, to begin enacting Reverberations, I would slip into the gallery nonchalantly, inhabiting the space with my gestures, almost as if I had been there all along. On the other hand, Two Brothers began with a loud call-and-response procession through the galleries: When the two performers exited the elevator they took down from the rehearsal space, they would call out, “Two brothers!” In response, the Museum staff and all those involved in the project would shout back, “Two Brothers!” Through the performers’ entrances, coupled with the virtuosity of how they negotiated suspension and gravity as they moved up, down, and around the poles, Two Brothers was an undeniable call to be seen and heard.

When the exhibition opened, the plan was for the two scores that emerged from the research residency to occupy the gallery separately at different times. However, as the exhibition went on, it became clear that Reverberations and Two Brothers needed to meet and overlap so that these two modes of performance could interpenetrate each other. On the last day of the exhibition, Brennan and Ryan decided to try a new ending to Two Brothers that resulted in Roz taking an entire thirteen minutes to make her way from the top of the pole to the floor. As Roz was slowly descending, I began enacting Reverberations. In this liminal space between ending and beginning, between two very different bodies participating in two kinds of events that required two very different forms of labor, I could feel the exhibition arrive. Had there been two more weeks of the exhibition, I would have been curious to see how these two performance scores might have continued to be in dialogue with one another, and how they could have potentially unsettled the ways in which our performative modes and tasks aligned or misaligned with expectations around our classed, raced, and gendered bodies.

Returning to “In Bed With…Andrea Fraser,” during the event, Andrea spoke about how she didn’t consider the people in her works characters, but more like positions inside a field of relations (an idea borrowed from sociologist and philosopher Pierre Bourdieu). By embodying their voices, she was able to navigate her own relationship to their positions within societal systems—her subjectivity. At least, that’s how I remember her describing it. While performing Reverberations, I would often shift the pronoun in that memory from “she” (Andrea) to “I.” “I don’t really think about their voices as characters, but more like positions inside a field of relations. Through the act of retelling, I’m trying to navigate my own subjectivity inside of this field.”

Lauren Bakst is a trained dancer and an artist whose work takes the forms of choreography, writing, performance, and video. Her most recent project “Living Room Index and Pool,” was an exhibition of installation and performance with artist Yuri Masnyj at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. Her current project Single Occupancy continues this collaboration, with performances at the Drawing Center this August as part of the Open Sessions exhibition “Name it by Trying to Name It.” Bakst teaches as part of the Thinking, Making, Doing curriculum at the School of Dance at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia. She is Managing Editor of the Movement Research Performance Journal and a contributing editor to BOMB magazine. Bakst regularly performs in the works of other artists, most recently those of Michelle Boulé, Gerard & Kelly, and Mariana Valencia. Bakst will be performing on Monday, August 24, in Timelining, a piece by Gerard & Kelly, as part of the exhibition “Storylines” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

This ten-minute-long video clip of Bakst performing Reverberations (2015) as part of Gerard & Kelly’s exhibition “P.O.L.E. (People, Objects, Language, Exchange)” in the New Museum’s Lobby Gallery begins and ends with her performing in the non-speaking modality. As Bakst connects with individuals and small groups of spectators, you can hear her shift into the work’s second modality. Combining speech and gestural recollections, she recounts the conversations from “In Bed With…” events and the movements from “Open Pole” sessions, all which are conflated with her own responses and those of audiences, past and present. View the video footage of Reverberations here. →

The other work by Gerard & Kelly that was performed as part of “P.O.L.E.” was Two Brothers (2015). This approximately twenty-minute-long score was performed by a crew of six performers that were matched in various configurations. Watch the duo of TyTy Love and Tyke Turner perform the first half of the score and the duo of Tanya St. Louis and Forty Smooth perform the second half here. →